This page contains the following sections:

When is surgical repair of an aortic dissection advisable?

How is repair of an aortic dissection accomplished?

What are the risks and benefits of such surgery?

What is involved in a typical recovery?

When is surgical repair of an aortic dissection advisable?

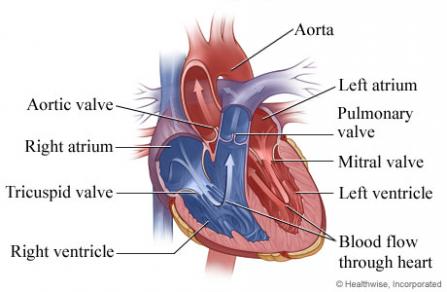

An aortic dissection—a split, tear, or weakened area in the lining of your body's main artery—is often a life-threatening condition and represents one of the rare true emergencies in cardiac surgery. Medication can sometimes be an appropriate treatment option for a dissection of the descending aorta. But immediate surgery will be advisable for nearly all dissections of the ascending aorta or aortic arch.

Once a dissection occurs in the ascending aorta, between 25% and 30% of patients die within hours, and the risk of death approaches 100% after a week without an operation. Our cardiac surgeons have long been known for their expertise in the repair of acute, emergency aortic dissections.

How is repair of an aortic dissection accomplished?

There are a number of ways to repair or replace the portion of an aorta damaged by a dissection. Which option is used will depend on such factors as where the dissection is located, how much of your aorta needs to be repaired or replaced, and the overall state of your health. Your surgeon will determine which of the following procedures is most appropriate in your particular situation:

- Open-heart surgery to repair an aortic dissection involves making a 7- to 10-inch incision over the middle of the sternum, or breastbone, then dividing the sternum to allow access to the heart. In some cases a less invasive option, involving a slightly smaller sternal incision, is possible. In either case, the actual repair involves replacing the damaged portion of your aorta with a graft — a tube the same size as your aorta, made of a durable artificial material such as Dacron, which is sutured, or sewn, into place.

It will be necessary to stop your heart from beating during the procedure, so the operation can be performed on a motionless and bloodless field; while your heart is stopped, a device known as a heart-lung bypass machine will take over your heart's function and maintain your circulation. Very occasionally, during complex operations involving replacement of a portion of the aorta, you may also be put into a state known as hypothermic circulatory arrest; this involves lowering your body temperature to significantly slow your body's cellular activity, permitting your blood flow to be temporarily stopped. (The term "hypothermic" comes from Greek words meaning "low heat," while "circulatory arrest" means your circulation is arrested, or stopped.) In other cases, a technique known as axillary cannulation (or the insertion of a drainage tube, known as a cannula, in an artery in your armpit, or axilla) can allow aortic replacement to be performed without hypothermic circulatory arrest; this advance may reduce the incidence of postoperative strokes and neurological deficits.

- Endovascular surgery may be an option for patients with a dissection of the descending aorta. This minimally invasive procedure involves making a couple of tiny incisions (often just 1 to 2 inches) in blood vessels in your groin; inserting long, thin tubes known as a catheters through the vessels to the point where your dissection is located; and then using X-ray guidance and long, thin instruments threaded through the catheters to place a little mesh tube known as a stent graft inside the affected portion of the vessel. (The term "endovascular" comes from Greek and Latin words meaning "within a vessel.")

In circumstances when it is appropriate, endovascular surgery can sometimes be done with the patient under local rather than general anesthesia; in addition, it does not require hypothermic circulatory arrest or use of a heart-lung bypass machine. Since this approach avoids the need to open the chest at all, it usually results in much faster healing.

- Valve-sparing surgery can be considered for operations on the part of the aorta closest to the heart, the aortic root. This procedure involves replacement just of the damaged portion of the vessel, not of the aortic valve as well; it is thus appropriate only for patients whose aortic valve is intact or repairable. The alternative is known as a composite graft, and it involves not only replacing the dissected portion of the aorta but also replacing the aortic valve with a mechanical valve.

What are the risks and benefits of such surgery?

It is important to keep in mind that every medical choice involves a trade-off between risks and benefits—whether it is to undergo surgery, take medication, or even just carefully monitor a condition (an option known as "watchful waiting").

In the case of an aortic dissection, however, especially of the ascending aorta or aortic arch, surgery will very often be the only viable option. As noted above, the risk of death approaches 100% after a week without operating on a dissection of the ascending aorta.

The risks involved in surgery are appreciable, but far lower than not operating. A given patient's risk will vary, depending on such factors as age and overall health status, but the average mortality, or risk of death, from repair of an aortic dissection is about 15%. Complications, such as a stroke, also occur in a certain percentage of cases, depending on the severity of the dissection; immediate surgery is often associated with better outcomes and fewer complications. In addition, any surgical procedure involves a very small risk of other complications, such as infection.

The benefits of a successful repair are many, with the majority of surviving patients returning to full productivity. Patients usually need to take medication for the rest of their life to control their blood pressure, so as to minimize pressure on the wall of their aorta. Close, long-term follow-up of such patients is also advisable, to watch for the development of complications or further dissections. Up to 30% of patients may require another operation to repair a subsequent dissection or aneurysm of their aorta.

What is involved in a typical recovery?

A typical open-heart procedure takes from 4 to 6 hours, in some cases up to 8 hours; patients are then maintained under general anesthesia for an additional 4 to 6 hours. If their heart is performing well and there is no excess bleeding, they can emerge from anesthesia and have their breathing tube removed. Most patients stay in the ICU until midday of the day after their procedure; if they continue to do well, the drainage tubes in their chest can then be removed and they can be moved to a regular hospital bed later that day.

The typical hospital stay ranges from 7 to 10 days, in some cases up to 14 days. At that point, the vast majority of patients are able to go home, with support from the visiting nurse service, though about 15% to 20% may need to spend some time in a rehab facility for more extensive rehabilitation. After discharge, patients are advised not to drive for about three weeks and not to lift anything heavier than 5 pounds for about 6 weeks. Beyond that point, they can resume their normal daily activities.

Patients tend to be surprised at how easy it is to control their pain. By the second day after their operation, most patients are comfortable without intravenous pain medication, taking only oral painkillers, and the overwhelming majority are discharged home on just Tylenol or Motrin.

In cases when minimally invasive surgery is appropriate, both the length of the operation and the recovery period are typically shorter (and much shorter in the case of endovascular surgery).

Page reviewed on: Jun 26, 2018

Page reviewed by: Jock McCullough, MD