When is surgical repair of a congenital heart defect advisable?

How is repair of a congenital heart defect accomplished?

What are the risks and benefits of such surgery?

What is involved in a typical recovery?

When is surgical repair of a congenital heart defect advisable?

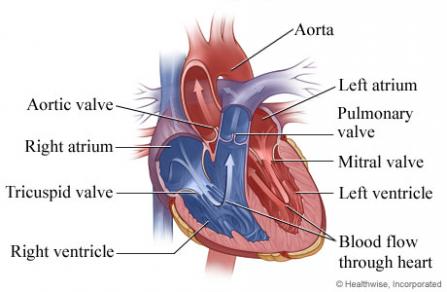

There are many different kinds of congenital heart defects—that is, abnormalities in the heart's structure present since birth. They vary significantly in their frequency and complexity, as well as in when symptoms first occur and how severe the symptoms are.

Very serious congenital heart defects must be treated in infancy, but some defects don't become a problem until many years later; or sometimes, a repair made in infancy requires re-repair in adulthood. We offer adult re-repair of congenital defects that were operated on in infancy or childhood, as well as repair of congenital defects that don't become evident until adulthood.

Your surgeon will evaluate the specifics of your situation and help you weigh the risks of surgery against the risks of managing the disorder with medication and other nonsurgical treatments. The advisability of surgical repair is highly variable and dependent entirely on the circumstances of each individual situation. However, an untreated congenital defect that has begun to cause symptoms may often lead to congestive heart failure.

Should you and your surgeon decide the time is right for surgery, keep in mind that we offer exceptional expertise in the surgical repair of congenital heart defects, as one of the surgeons on the team is fully trained in the repair of adult congenital heart defects and has more than 20 years of experience in performing such repairs.

How is repair of a congenital heart defect accomplished?

There are almost as many ways to repair congenital heart defects as there are such defects. In some cases, however, the repair or re-repair in adulthood of a congenital defect is similar to the repair of acquired diseases on the same part of the heart. Your surgeon will be able to explain in detail the exact process by which your repair will be accomplished.

Congenital heart defects are typically repaired via open surgery. In some cases, however, such procedures can be accomplished using minimally invasive techniques. The appropriate approach depends on many factors, from the specifics of your defect to the overall state of your health. These are the primary options; your surgeon will determine which one is best in your particular situation:

- Open-heart surgery involves making a 7- to 10-inch incision over the middle of the sternum, or breastbone, then dividing the sternum to allow access to the heart. In some cases a less invasive option, involving a slightly smaller sternal incision, is possible. Then the congenital defect is repaired or re-repaired.

It will be necessary to stop your heart from beating during the procedure, so the operation can be performed on a motionless and bloodless field; while your heart is stopped, a device known as a heart-lung bypass machine will take over your heart's function and maintain your circulation. Very occasionally, during complex operations involving the aorta, you may also be put into a state known as hypothermic circulatory arrest; this involves lowering your body temperature to significantly slow your body's cellular activity, permitting your blood flow to be temporarily stopped. (The term "hypothermic" comes from Greek words meaning "low heat," while "circulatory arrest" means your circulation is arrested, or stopped.) In other cases, a technique known as axillary cannulation (or the insertion of a drainage tube, known as a cannula, in an artery in your armpit, or axilla) can allow aortic replacement to be performed without hypothermic circulatory arrest; this advance may reduce the incidence of postoperative strokes and neurological deficits.

- Minimally invasive surgery involves making one or two much smaller incisions (typically 2 to 4 inches) in the side of your chest, between your ribs. Then the repair is performed by inserting an X-ray camera and long, thin surgical instruments to the point where the congenital defect is located. Minimally invasive surgery also requires the use of a heart-lung bypass machine. In circumstances when it is appropriate, this approach avoids the need to split the sternum and open the entire chest, so recovery may be faster.

What are the risks and benefits of such surgery?

It is important to keep in mind that every medical choice involves a trade-off between risks and benefits—whether it is to undergo surgery, take medication, or even just carefully monitor a condition (an option known as "watchful waiting").

In the case of the repair or re-repair of a congenital heart defect, deciding whether surgery is advisable involves balancing the risks involved in any heart surgery against the risk that managing the disorder with medication and other nonsurgical treatments may result in progressive damage to your heart and circulatory system.

The risks involved in surgery are typically fairly low; your surgeon will be able to explain the likelihood of complications given the particulars of your situation, including your age and the overall state of your health. In general, however, the risk of mortality, or death, from cardiac surgery is quite low. Heart surgery is also associated with a small risk of a blood clot that causes a serious stroke. And any surgical procedure involves a very small risk of other complications, such as infection.

Patients who smoke can reduce their risk of complications if they stop smoking at least 2 to 4 weeks before their surgery (it is best not to quit immediately before having heart surgery, however, because when people stop smoking they often have short-term bronchorrhea, or excess secretions in their respiratory tract, which makes them cough a lot—and coughing a lot when you have just had heart surgery is not a good idea).

The benefits of successful surgery are usually considerable; your surgeon will be able to explain the likely outcome in your case.

What is involved in a typical recovery?

A typical open-heart procedure takes from 4 to 6 hours, in some cases up to 8 hours; patients are then maintained under general anesthesia for an additional 4 to 6 hours. If their heart is performing well and there is no excess bleeding, they can emerge from anesthesia and have their breathing tube removed. Most patients stay in the ICU until midday of the day after their procedure; if they continue to do well, the drainage tubes in their chest can then be removed and they can be moved to a regular hospital bed later that day.

The typical hospital stay ranges from 4 to 7 days. At that point, the vast majority of patients are able to go home, with support from the visiting nurse service, though about 15% to 20% may need to spend some time in a rehab facility for more extensive rehabilitation. After discharge, patients are advised not to drive for about three weeks and not to lift anything heavier than 5 pounds for about 6 weeks. Beyond that point, they can resume whatever activities they wish to.

Patients tend to be surprised at how easy it is to control their pain. By the second day after their operation, most patients are comfortable without intravenous pain medication, taking only oral painkillers, and the overwhelming majority are discharged home on just Tylenol or Motrin.

In cases when minimally invasive surgery is appropriate, both the length of the operation and the recovery period are typically shorter.

Page reviewed on: Jun 26, 2018

Page reviewed by: Jock McCullough, MD