This page contains the following sections:

When is repair or replacement of a pulmonary or tricuspid valve advisable?

How is repair or replacement of a pulmonary or tricuspid valve accomplished?

What are the risks and benefits of such surgery?

What is involved in a typical recovery?

When is repair or replacement of a pulmonary or tricuspid valve advisable?

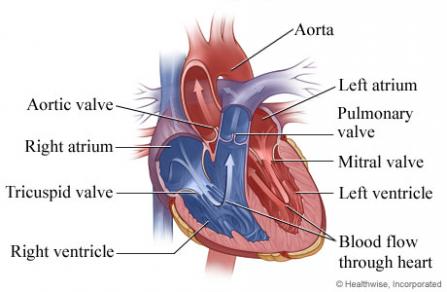

Repair or replacement of the pulmonary valve or of the tricuspid valve is far less common than repair or replacement of the aortic and mitral valves, your heart's two other valves. Surgery on the pulmonary valve is sometimes performed on a stand-alone basis, but surgery on the tricuspid valve is typically undertaken only in conjunction with surgery on one of the other two valves, most often a repair of the mitral valve.

Both the pulmonary valve and the tricuspid valve are made up of three little flaps of tissue that control the flow of blood from one part of your circulatory system to another; the flaps are also known as leaflets or cusps. (The term "cusp" comes from a Latin word meaning "point," a reference to the fact that the flaps in both valves are triangle-shaped.)

If you are diagnosed with a damaged pulmonary or tricuspid valve, your surgeon will evaluate the specifics of your situation—especially how badly damaged your valve is and how serious your symptoms are. Then it will be possible to weigh the risks of surgery against the risks of managing the disorder with lifestyle changes and medication. In most circumstances, it will be advisable to manage your condition with nonsurgical treatments until it is necessary to perform heart surgery for some other reason. But in rare circumstances, it may be advisable to consider stand-alone surgery on a damaged pulmonary or tricuspid valve.

In either case, it is usually preferable to repair rather than replace the damaged valve, because a repaired valve generally results in better heart function, better resistance to infection, and better long- and short-term survival.

Should you and your surgeon decide the time is right for surgery, keep in mind that valve repair and replacement surgery is a particular specialty of our cardiac surgeons. They even have considerable expertise in these less common valve procedures.

How is repair or replacement of a pulmonary or tricuspid valve accomplished?

Your surgeon will first determine whether it will be possible to repair your damaged pulmonary or tricuspid valve, or whether it must be replaced. There are two primary ways of repairing a damaged valve; these procedures are sometimes performed separately and sometimes in combination:

- Annuloplasty involves repairing the ring of tissue to which the flaps are attached (this ring is known as the annulus), by attaching a ring of tissue, cloth or metal to it.

- Resection involves trimming and/or reshaping the flaps themselves.

If it is necessary to replace rather than repair the valve, there are two primary kinds of replacement valves. Factors such as your age and the overall state of your health will affect which kind is most appropriate:

- Mechanical valves are made of very durable artificial materials, such as titanium, carbon, polyester, Dacron or Teflon. They are typically very long-lasting; however, use of a mechanical valve usually requires patients to take blood-thinning medication (often referred to by the brand name of Coumadin) for the rest of their lives.

- Biological valves, also known as tissue valves or bioprosthetic valves, are made of animal tissue, often from a pig or a cow. They do not usually necessitate the use of blood-thinning medication; however, biological valves typically last only 10 to 20 years, so a second valve replacement operation may be required in the future.

Because surgery on the pulmonary or tricuspid valve is almost always performed in conjunction with another cardiac procedure, usually a repair of the mitral valve, the requirements of that operation typically determine which surgical approach is best. Open-heart surgery is the most common option for mitral valve repairs, but your surgeon will decide which of the following procedures is most appropriate in your particular situation:

- Open-heart surgery involves making a 7- to 9-inch incision over the middle of the sternum, or breastbone, then dividing the sternum to allow access to the heart. In some cases a less invasive option, involving a slightly smaller sternal incision, is possible. Then the damaged valve is either repaired or replaced. It will be necessary to stop your heart from beating during the procedure, so the operation can be performed on a motionless and bloodless field; while your heart is stopped, a device known as a heart-lung bypass machine will take over your heart's function and maintain your circulation.

- Minimally invasive surgery involves making one or two much smaller incisions (typically 2 to 4 inches) in the side of your chest, between your ribs. Then the procedure is performed by inserting a tiny camera and long, thin surgical instruments through your tissues to the damaged valve. Minimally invasive surgery also requires the use of a heart-lung bypass machine. Although it is typically not the preferable option for valve repairs, in circumstances when it is appropriate this approach avoids the need to split the sternum and open the entire chest, so recovery may be faster.

What are the risks and benefits of such surgery?

It is important to keep in mind that every medical choice involves a trade-off between risks and benefits—whether it is to undergo surgery, take medication, or even just carefully monitor a condition (an option known as "watchful waiting").

In the case of surgery on a damaged pulmonary or tricuspid valve, deciding whether surgery is advisable involves balancing the risks involved in any heart surgery against the risk that continuing to manage the disorder with medication and other nonsurgical treatments may result in progressive damage to your heart and circulatory system.

The risks involved in surgery are quite low. Since pulmonary or tricuspid valve surgery is usually undertaken at the same time as another surgical procedure, the overall risks are generally the same as for whatever other procedure is being performed—typically a mitral valve repair, but sometimes a mitral valve replacement or an aortic valve repair or replacement.

The benefits of successful surgery are considerable. The overwhelming majority of patients, once they recover, feel better than they did before the operation, experience relief of their symptoms, and are able to resume any activities they wish to engage in. In most cases, successful valve surgery also results in improved survival rates.

What is involved in a typical recovery?

A typical open-heart procedure takes from 4 to 6 hours, in some cases up to 8 hours; patients are then maintained under general anesthesia for an additional 4 to 6 hours. If their heart is performing well and there is no excess bleeding, they can emerge from anesthesia and have their breathing tube removed. Most patients stay in the ICU until midday of the day after their procedure; if they continue to do well, the drainage tubes in their chest can then be removed and they can be moved to a regular hospital bed later that day.

The typical hospital stay ranges from 4 to 7 days. At that point, the vast majority of patients are able to go home, with support from the visiting nurse service, though about 15% to 20% may need to spend some time in a rehab facility for more extensive rehabilitation. After discharge, patients are advised not to drive for about three weeks and not to lift anything heavier than 5 pounds for about 6 weeks. Beyond that point, they can resume whatever activities they wish to.

Patients tend to be surprised at how easy it is to control their pain. By the second day after their operation, most patients are comfortable without intravenous pain medication, taking only oral painkillers, and the overwhelming majority are discharged home on just Tylenol or Motrin.

In cases when minimally invasive surgery is appropriate, both the length of the operation and the recovery period are typically shorter.

Page reviewed on: Jun 26, 2018

Page reviewed by: Jock McCullough, MD