This page contains the following sections:

When is a coronary artery bypass graft advisable?

How is a coronary artery bypass graft accomplished?

What are the risks and benefits of such surgery?

What is involved in a typical recovery?

When is a coronary artery bypass graft advisable?

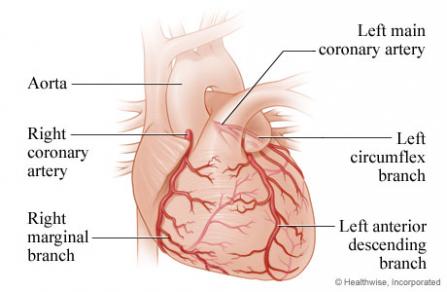

A coronary artery bypass graft (also known as a CABG, pronounced like "cabbage," or as bypass surgery) involves creating a new pathway for blood to flow around a blockage in one or more of the arteries that supply the heart itself with blood; these are known as your coronary arteries. CABG surgery is the most-often-performed kind of open-heart procedure in the U.S. Bypass operations have been more extensively performed and more extensively studied than any other cardiac operation in the country, ever since the procedure's inception in the 1960s.

It is a highly effective treatment for a condition known as coronary artery disease (CAD) or coronary heart disease—a blockage in the coronary arteries that is usually due to a problem called atherosclerosis; atherosclerosis is caused by the progressive buildup of plaque, or deposits of cholesterol, inflammatory cells and other substances on the arterial walls. In some situations—such as when a major heart attack is determined to have been caused by CAD or when CAD is causing severe symptoms involving multiple coronary arteries—coronary artery disease may be life-threatening, and emergency bypass surgery may be required.

CABG surgery may also be considered in cases of severe angina or congestive heart failure. These situations are less apt to represent an emergency. Your surgeon will likely be able to take the time to evaluate the specifics of your situation and help you weigh the risks of bypass surgery against the risks of continuing to manage your angina or congestive heart failure with medication and other nonsurgical treatments.

Should you need CABG surgery on an emergency basis, or should you and your surgeon decide the time is right for bypass surgery, keep in mind that our cardiac surgeons have considerable expertise in performing this very common procedure.

How is a coronary artery bypass graft accomplished?

The basic premise of CABG surgery is that healthy blood vessels from elsewhere in your body—most often, veins from your legs and/or mammary arteries from your chest—are used to replace your blocked coronary arteries. The procedure can be performed on just one coronary artery or on several at the same time; you may hear bypass surgery called a "two-way bypass" or "double bypass," for example, or a "four-way bypass" or "quadruple bypass"—this is a reference to the number of arteries involved.

The term "bypass" in the procedure's name means your circulation will bypass, or be routed around, the blocked portions of your coronary arteries. And "graft" is a term used to describe the transplantation of living tissue (in this case, some of your own blood vessels) from one place to another. You may also hear a couple of other terms in references to bypass surgery. An "anastomosis" is a surgical connection between one tubular organ and another—in the case of a CABG, between your coronary arteries and the veins or arteries from elsewhere in your body. And "revascularization" means re-establishing an adequate flow of blood to a part of the body that has suffered from a poor blood supply (a condition known as ischemia, which comes from a Latin word meaning "stopping blood"). In other words, CAD results in cardiac ischemia, or a poor supply of blood to your heart, while a CABG results in revascularization, or the restoration of a good blood supply, thanks to a procedure involving anastomosis.

The vessels used in a CABG procedure can be either veins or arteries and can come from several locations, including your legs, arms, and/or chest. In all cases, your circulatory system is able to compensate for the removal and repurposing of the vessels. The source or sources your surgeon decides on will depend on many factors, including how many of your coronary arteries must be bypassed and the overall state of your health. Most often, bypass grafts are performed using veins from your legs and/or one or both of your mammary arteries—the arteries that supply your chest with blood.

Studies have shown that the optimal source for bypass grafts is the mammary arteries, because they are less likely to suffer reblockage than vein grafts and thus result in better long-term survival. We have one of the highest rates in northern New England for utilization of bilateral mammary arteries ("bilateral" means "from both sides").

A bypass procedure typically involves both open-heart surgery and endoscopic surgery. It will usually be necessary to stop your heart from beating during the procedure. A device known as a heart-lung bypass machine will be used to maintain your circulation during this time.

The endoscopic portion of the operation involves making a couple of tiny incisions (often just 1 to 2 inches) in your leg. Then an endoscope, a flexible tube with a camera on its tip, and long, thin surgical instruments are inserted through the incisions, allowing the surgeon to "harvest" veins from your legs.

The open-heart portion of the operation involves entering the chest cavity by dividing the sternum, or breastbone, separating the muscles of the chest wall, and accessing your heart through a large incision (typically 5- to 7- inches, and sometimes up to 10 inches) in your chest. The procedure itself involves suturing, or sewing, the harvested leg veins and/or rerouted mammary arteries into place so the flow of blood from your aorta to your heart itself goes through these newly placed vessels rather than through the blocked portions of your coronary arteries. It will be necessary to stop your heart from beating during the procedure, so the operation can be performed on a motionless and bloodless field; while your heart is stopped, a device known as a heart-lung bypass machine will take over your heart's function and maintain your circulation.

What are the risks and benefits of such surgery?

It is important to keep in mind that every medical choice involves a trade-off between risks and benefits—whether it is to undergo surgery, take medication, or even just carefully monitor a condition (an option known as "watchful waiting").

In the case of CABG, deciding whether surgery is advisable is sometimes an emergency, life-or-death matter. But sometimes, it involves balancing the risks involved in any heart surgery against the increasing likelihood that your symptoms of CAD, angina or congestive heart failure will worsen. Patients with severe CAD, for example, have a 35% to 50% risk of dying within five years of their diagnosis if they don't have bypass surgery.

The risks involved in surgery are far lower. A given patient's risk will vary, depending on such factors as age and overall health status, but the average mortality, or risk of death, from bypass surgery is from 1% to 2%. Bypass surgery is also associated with a risk of between less than 1% and 2% of a blood clot that causes a serious heart attack or stroke. And any surgical procedure involves a very small risk of other complications, such as infection.

The risks are typically higher when bypass surgery must be performed on an emergency basis. But in nonemergency situations, patients who smoke can reduce their risk of complications if they stop smoking at least 2 to 4 weeks before their surgery (it is best not to quit immediately before having heart surgery, however, because when people stop smoking they often have short-term bronchorrhea, or excess secretions in their respiratory tract, which makes them cough a lot—and coughing a lot when you have just had heart surgery is not a good idea).

The benefits of a successful repair are considerable. The overwhelming majority of patients who undergo bypass surgery, once they recover, feel better than they did before the operation and are able to resume any activities they wish to engage in. Bypass surgery typically reduces patients' symptoms of angina and risk of having a heart attack and increases their survival.

What is involved in a typical recovery?

A typical CABG procedure takes from 4 to 6 hours, in some cases up to 8 hours; patients are then maintained under general anesthesia for an additional 4 to 6 hours. If their heart is performing well and there is no excess bleeding, they can emerge from anesthesia and have their breathing tube removed. Most patients stay in the ICU until midday of the day after their procedure; if they continue to do well, the drainage tubes in their chest can then be removed and they can be moved to a regular hospital bed later that day.

The typical hospital stay ranges from four to seven days. At that point, the vast majority of patients are able to go home, with support from the visiting nurse service, though about 15% to 20% may need to spend some time in a rehab facility for more extensive rehabilitation. After discharge, patients are advised not to drive for about three weeks and not to lift anything heavier than 5 pounds for about 6 weeks. Beyond that point, they can resume whatever activities they wish to.

Patients tend to be surprised at how easy it is to control their pain. By the second day after their operation, most patients are comfortable without intravenous pain medication, taking only oral painkillers, and the overwhelming majority are discharged home on just Tylenol or Motrin.

Page reviewed on: Jun 26, 2018

Page reviewed by: Jock McCullough, MD